More active older age is in our common interest

In the hundred years after the 1880s, state pension systems were developed, offering people the possibility of both an increasingly early retirement and a good income for those who did not work anymore. At the end of the 20th century, ‘so-called’ developed countries found that there was no longer enough money for retired people. According to a recently published retirement readiness study from SEB, the majority of Estonian people still expect their retirement income to amount to almost 90% of their last salary, including the 50% state pension amount.

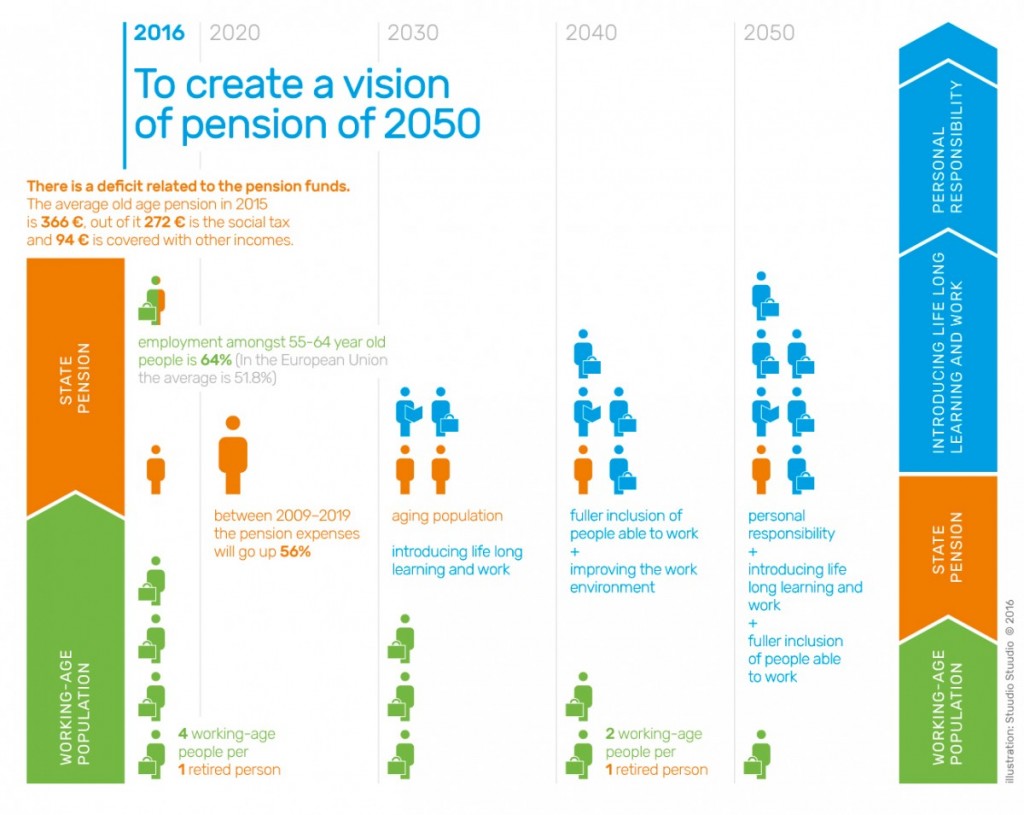

It’s time to wake up and understand that this will never happen. We must work hard to be able to guarantee even a current level of income for retired people. But even now the pension fund is negative. If we could merely pay pensions from the collected social tax, the average old-age pension in Estonia would be 270 Euros. But it isn’t so because we have decided to finance the pension fund’s negative budget from other sources of national income. It is a right and good decision to ensure that pensioners get by, but with the change in the proportion of older people to people of working age (today, there are four working-aged people for each pensioner; by 2040 there will be only two), we will spend an increasing amount of money on social benefits, and less money will be spent on national development. Nobody wants to be in a situation where we have to agree that the state is there simply to pay pensions.

The ministers in the Ministry of Social Affairs spoke at the beginning of the year that the pension issue must be dealt with, but it’s not an actual current political issue because the retirement age has been set until 2025. So there’s no crisis. I’d like to hope that this issue won’t become a sequel to the “Ensuring the sustainability of health insurance” saga, when a problem that was discussed at length for six years was not dealt with and resolved, because… there was no hurry. But the “pain” will not go away, so conceptual decisions are required to change the structures in both the health insurance and pension systems.

Estonian Cooperation Assembly has set the goal of creating the vision of a pension in 2050, so we are dealing with this topic from the beginning of this year.

Similar problems in other countries

Last year, the OECD unveiled its “Pensions at a Glance 2015” data set, which outlines the major challenges for developed countries: 1) whether and for how long people are ready to work; 2) Abolition of the current early retirement options; 3) The implementation of lifelong learning and working; 4) Improvement of the working environment in order to avoid the risk of premature work retirement.

There are two main ways of discussing retirement insurance and the future – the impact on state costs and how it ensures an income for retired people. Retirement system sustainability issues, however, will not mean and cannot mean merely whether we as a nation can maintain this system, or even what kind of system we can maintain? Attention should be paid to aspects highlighted by the OECD, which means answering how we can reshape our society so that we can and would like to work for as long as possible.

In January, Ene-Margit Tiit wrote in the Postimees newspaper that talking about pensions in the future is the easiest way to calculate how many people of working age there will be for every retired person. But elderly people, after all, are supported not by actual persons but rather by the money they have earned. So, a reasonable goal would be to talk about the full utilisation of existing working hands, and all the more effective, higher-value-added work of all the inhabitants of Estonia.

Lifelong learning as a way of thinking

In addition, the OECD report shows that there may be longer pauses in careers than before since having a career nowadays doesn’t necessarily mean that a person works in one place, or even in the same profession for a lifetime. In the Estonian context, this means a loss of blue-collar jobs because machines and/or sharing services are more effective. If these people lose their jobs, it is important for the pension system for two reasons: 1) they need support from the state, which means costs; 2) if these people do not enter the labour market, they don’t collect the capital required for a pension.

Estonian Lifelong Learning Strategy 2020 states that learning should become an integral part of an active lifestyle, among older people too. Researches show that many younger people are involved in lifelong learning, but this involvement decreases at a certain age. One reason is the lack of interest of employers to contribute to older people. If people would work longer, there would not be a reason to leave them without learning. A set of articles entitled “A glance at the grey area” was recently published that analysed the situation of older people in Estonia and showed, among other things, that our learning capacity in older age does not actually decrease, so there’s no reason to omit any people from learning due to age. Of course, there are the differences in the learning process – children and adults should be taught in different ways – but this is just a pretext rather than the cause. Besides, continuous development improves people’s quality of life.

Estonia has a number of advantages

Therefore, we need to study and work more in the future; fortunately, Estonia has a number of advantages over other countries.

Estonia has a high employment rate among older people. Approximately 62% of 55-64 year olds are employed; the OECD average is less than 60%. At the same time, there are countries where three-quarters of older people are in employment (Norway, Iceland). Of course, the high employment rate in Estonia is related to the low pension, but researches have shown that the willingness to work exists in every case. Whatever reasons exist today, we have to build our future on it. If their health permits, people want to work.

Also, people have the will and readiness to increase personal responsibility in the shaping of retirement, but few real steps have been taken. Property or continued work are informally regard as pension, but the only real estate is their own home, and despite high level of employment among older workers many of them still leave the labour market prematurely. It is no secret that while our retirement age is above 60 years, the average retirement age is still under 60.

Pension 2050

There is a slogan in English: “40 is the new 30”! Scientists Sanderson and Scherbov in 2008 in the article “Rethinking Age and Aging” proposed that human age can’t be measured on the basis of years lived or on the basis of statistically remaining years. This means, however, that a person in his 40s today is equivalent to a thirty-year-old 50 years ago. Therefore, people’s living and working time has changed: A 60-year-old person today is very valuable to the labour market due to their skills and life experience. Let’s not forget here that the number of working age population will have already decreased by 50,000 by 2020. The easiest way we have to compensate for the lack of working hands is to increase the employment level among older persons. How to do it – isn’t it a question for public discussion?

Therefore, retirement today no longer means a biological or chronological age, and it’s wrong to speak about elderly people as being a single group of people 65 years and older. Human cognitive capability or the ability to understand, learn and remember are much more important. As mentioned in “A glance at the grey area”, the cognitive capacity of elderly people in Estonia compared to other countries is quite average. Cognitive performance decreases with age, but also with active life, e.g. quitting work. Therefore, continuous learning and working is useful in many different ways.

Estonian Cooperation Assembly has started to create a vision of the pension system in 2050. A prerequisite for this is a public debate over how we see a more mature person after every 40-50 years. Such discussions haven’t been held yet in Estonia, and we hope that simply saying young people do not understand and old people are not able will not work this time. Instead, we hope to harness the wisdom of the elderly and initiative of young people and design a pension system according to the 21st century reality. As the Estonian Employers’ Confederation President Toomas Tamsar said in early March at the “Kite Fly 2016” conference, more active older age is in our common interest.

See original article in Estonian, published in Eesti Päevaleht (30th of March 2016)